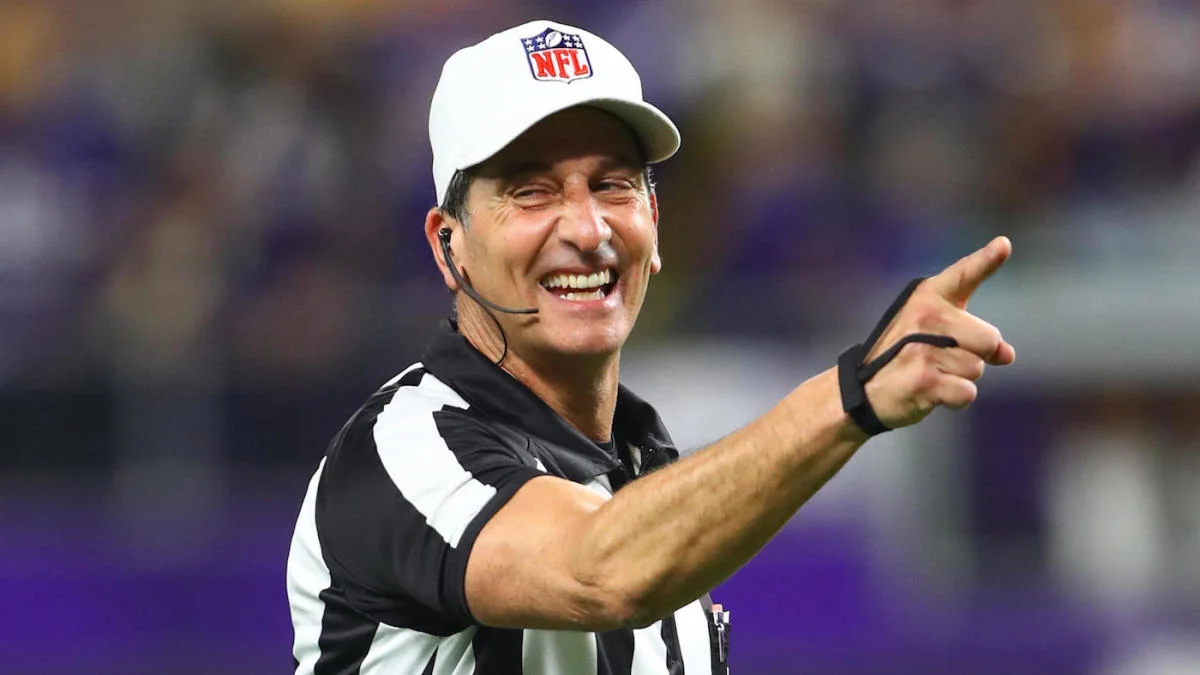

Gene Steratore’s officiating career culminated in being the referee of the biggest game in football, but it took him a long time to reach that mountaintop. As both an NFL and college basketball referee, his life was full of non-stop traveling and nights entailing three hours of sleep. However, it was all worth it to him in the end.

So, how did Steratore become such a successful referee? The answer is a love of officiating that started from a young age. Before Steratore would go on to officiate the NFL and NCAA Men’s Division I basketball in front of millions of fans, he started refereeing games at the local level.

“My dad [Gene Steratore, Sr.] was part of the first group of officials for the Big East when it was formed in 1980. So, I grew up with it in my home. I refereed my first basketball game with the YMCA in Uniontown when I was 13,” Steratore said. “Asbury played Central Christian in a fifth grade girls game, and it was one of the scariest things I ever did in my officiating career. But, I was hooked from that point on.”

Although Steratore did not know it at the time, he was beginning his journey to officiate the biggest game in American sports. Along the way, he developed a strong mentality that guided his career.

“In officiating, the best compliment you can get is that you weren’t recognized. Officiating games in front of millions of people every night requires that you know your goal is to do the right thing for the game, even if you aren’t appreciated for all the stuff you did right. But, if you make a human error, because we are all imperfect, you know you’ll be chastised and ridiculed for it,” Steratore said.

This philosophy helped him develop the strength of mind needed to officiate games at the highest level, and reflecting on his time in the NFL, it also helped him handle the intense scrutiny the league has for its officials. A common misconception people may have about NFL officials is that they show up for games, officiate them, and go home until it is time for the next game, but that could not be further from the truth.

Working as an official in the NFL entailed roughly a 30-hour week. Generally, Monday and Tuesday were spent reviewing the previous game and navigating through the NFL’s referee grading system from the league office. All seven officials on an NFL field are graded from three different angles (sideline, end zone, and television) on every play of every game. Those angles are all saved on an official’s individual Zip drive that is given to them on Monday morning to be reviewed.

“[NFL official graders] watch every play a minimum of seven times because every official in football only has a responsibility for two or three players (or a certain area). For example, I never saw Dez Bryant catch the ball. I only saw it under replay,” Steratore said, referring to Bryant’s overturned catch in the 2014 NFC Divisional Playoff game. “When I was an NFL official, if you made six or seven mistakes throughout the whole season, you probably didn’t get a playoff game. You had to be right about 98.3% of the time.”

On top of his NFL workload, Steratore also officiated about 80 NCAA men’s basketball games during the NFL season, and neither the NFL nor the NCAA appreciated him refereeing for the other organization. Steratore had to make many sacrifices to keep up his lifestyle, but he could not resist the personal challenge that it brought to him.

On Steratore’s X (formerly Twitter) page, his pinned tweet is a 2018 quoted tweet from the Big Ten Network. It is a microcosm of his officiating career, going from refereeing the Minneapolis Miracle to a Minnesota-Penn State game in Happy Valley.

“I’m probably the last guy crazy enough to officiate both sports. The process psychologically and emotionally consumed several men and women I’ve worked with just in the NFL alone,” Steratore said.

Along with the stress brought on by four to five college basketball games and an NFL game every week, Steratore also took great pride in managing the stress brought on by the screaming of coaches from the sideline after a call.

“I felt that it was such an amazing practice in self-control. The majority of the time coaches weren’t right about what they were talking about, but the art of it is diffusing that highly heated situation. Because, about 80% of what they were saying was emotional, one-sided thought,” Steratore said.

Steratore got it down to such a science that he knew the exact time when a camera would focus on him after making a call and a coach started yelling.

“I knew I had about five to seven seconds to hopefully diffuse this completely adolescent, profanity-laced behavior and I had several tricks that I used to help diffuse them. When I had a coach come running 10 yards onto the field in football, I would walk over to him knowing that TV was on me,” Steratore said. “I would tell him to meet me at his sideline, and when he followed me like a good duckling, I’d tell him he could say all that he wanted to say, but after I responded, that would be the end of the conversation.”

During those 15 seconds of television, Steratore did his part to show empathy for coaches, while also having the awareness to hold those coaches, his fellow officials, and himself accountable to protect the integrity of the game. For Steratore, the idea of empathy and awareness to protect the integrity of the game extended to holding spectators accountable, too. He recalled an instance where he had to interject to stop a fan from harassing him.

“I would know the rhythm of the guy’s yelling, and I wanted to be patient with him. Later, I would spin on that mid-sentence, and I would briefly make eye contact with him. Because he was human and embarrassment set in, he’d shut down right away,” Steratore said, “All the people around him were not entertained by his profanity, and he was ruining a lot of their experiences that night, so in doing that I did the game and the spectators a good service.”

Despite that, as a referee, there was only so much that Steratore could do to assuage coaches and spectators. There were specific circumstances that people were mad at him regardless of what call he made. Especially since the advent of instant replay as a tool to help referees make calls, officials like Steratore have been put under the microscope, even receiving death threats.

“I had a retired FBI agent that was my own personal security person that met my family and anybody that was close to me. He drove past my house once or twice a week in a plain red car,” Steratore said. “On occasion, my kids were removed from college for three or four days at a time because people would make death threats toward myself and my family.”

One of those calls made with the assistance of instant replay late in games was the infamous Calvin Johnson ‘catch’ back in 2010. With 24 seconds left in the game, Detroit quarterback Shaun Hill found Calvin Johnson in the end zone for what appeared to be a go-ahead touchdown. However, upon further review, Steratore called it an incomplete pass.

“Because technology wanted to come into the human element, we had to decide when a catch finally ended. During my Calvin Johnson play, there was no interaction with the NFL office in New York like they do today, so it was just the replay official and me making the call,” Steratore said. “I told the replay official that it’s a catch but he told me that he had to go through all these things to finish the process of the catch. I wasn’t extremely happy that someone was telling me all these nuances to define a catch, but he was smart enough to know that’s how the NFL wrote this replay situation.”

The Calvin Johnson ‘catch’ had massive repercussions on the definition of a catch in the NFL for the next seven years, but it also gave rise to the prominence of the rules analyst position (Steratore’s current job) that is on every NFL broadcast today.

“Mike Pereira hired me as a referee, and the irony of it was that the first game Pereira was a rules analyst for was the Calvin Johnson game. While I was under the hood, the announcers brought Pereira in and he gave this wishy-washy statement, which I’m kind of learning myself. But then, Brian Billick pressed Pereira, telling him that he was hired to say what he thought (not what I thought),” Steratore said. “And just before I clicked the mic on, Pereira said I was going to say incomplete, which I did. Literally, he got a three-year extension that day, and that play started what became a future job for me.”

Ironically, Steratore and Pereira did not meet again in person until 2014. Steratore joked with Pereira during breakfast the day of the 2014 NFC Divisional Playoff game between the Cowboys and Packers that he was glad that they would not have to go through a Calvin Johnson ‘catch’ scenario again; but, even the Dez Bryant ‘catch’ game was not the last time instant replay would determine the outcome of a major call for Steratore.

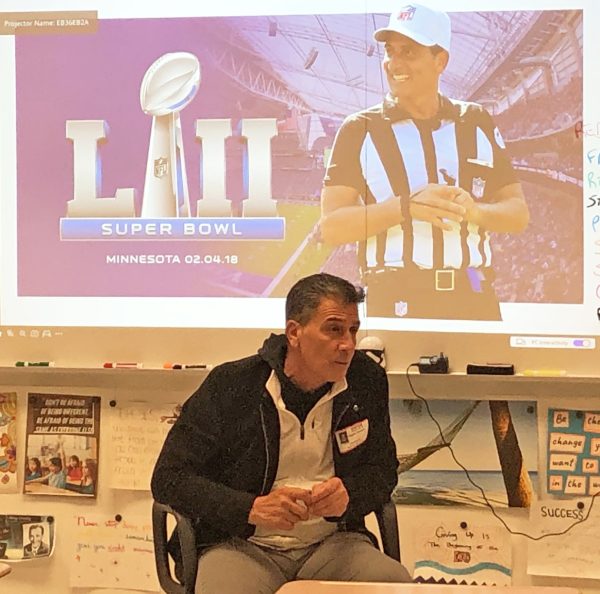

That last time for Steratore would occur in his final game: Super Bowl LII. For football players, Super Bowl Sunday is an event unlike any other, and for Steratore, his preparation for the 2018 Super Bowl and the secrecy of it was unlike any other.

“You’re wired when you referee a Super Bowl from three hours before kickoff until you get in the shower after. So, everything I said for seven hours is taped on NFL Films. They have not released all of it because they can’t. People have to retire and die (probably me being one of them) before you all get to hear everything,” Steratore said.

Late in the fourth quarter, quarterback Nick Foles threw the game-winning touchdown pass to tight end Zach Ertz to put the Philadelphia Eagles ahead of the New England Patriots with 2:21 remaining. However, it was uncertain that Ertz maintained control of the ball crossing the goal line, so it went to instant replay.

“The NFL was telling me in my headset that he didn’t survive the ground and it was incomplete. But, they just showed him in the air. In the process of replay, you have to see the whole play. You can’t just go to the last part of it,” Steratore said. “So, I saw the play from the beginning and had a longer than normal conversation on the field of the Super Bowl defining what I just watched, telling about 10 people from the NFL, who were all my supervisors, that this is a touchdown.”

After going through another dramatic instant replay ordeal, Steratore joked at the time that it was time to retire from the NFL.

“Calvin didn’t catch it. Dez didn’t catch it. Zach Ertz caught it, and I figured that this was my ticket to retire because someone finally caught it,” Steratore said.

In true Steratore fashion, he went on to referee a basketball game the next day at Northwestern University against the University of Michigan, before retiring in June of 2018.

After retiring from officiating, Steratore was hired by CBS as a rules analyst. During the Elite Eight game between San Diego State and Creighton last year, Steratore was tasked with breaking down the ending sequence of SDSU’s 57-56 victory.

When a play like the SDSU-Creighton foul happens, Steratore will hear in his earpiece that the producers are sending him to a certain game, and he will get about 20 seconds to watch the play, digest it, and push a button that allows him to talk to millions of people.

Steratore needs to know announcers, referees’ names, the city the game’s played in, and be able to quickly and accurately determine the correct call before jumping to the next game. Especially during March Madness, it is incredibly stressful because, at its peak, Steratore works 13 hours straight.

After the SDSU-Creighton game specifically, Steratore had to hurry down to Studio 43 from his own studio to do a post-game analysis at the CBS Broadcast Center.

“Within 30 seconds of the game ending, I heard my producer tell me that I needed to be downstairs on the table with Jay Wright, Charles Barkley, and company. I needed to be dressed in my suit, run downstairs, get rewired, and explain that play in 45 seconds,” Steratore said. “So, after my staff frantically dressed me like a scarecrow, I hustled down there, and the producers made sure I was ready to go on the air. Right before I sit down, Charles looks at me and goes, ‘That ain’t no damn foul, bruh.’ I told Chuck not to start this with me and that we could talk later tonight, not live on national television.”

Steratore enjoys his current job as a rules analyst, but he also emphasized the shortage of officials across the country. They have to work in a much more toxic environment today than when Steratore was younger and social media did not exist.

“The reason why a lot of people don’t want to ref right now is because they see referees getting attacked, especially on the internet. People on the internet can be much more vicious on their phone than they can be face-to-face,” Steratore said. “Unfortunately, because of how things have evolved, a lot of people like this [expletive], which feeds into those individuals. So when they go to games, they feel like they can call those refs things that they wouldn’t even think of saying before.”

While officials like Steratore often face criticism and ridicule from media outlets and individuals at a national level, even referees at a local level must regularly handle harassment.

“Whether you come out of the locker room in front of eight people or 80,000, almost instantly, you’re not really liked. This uniform and this position puts me in a place where the majority of people are thinking that me, this one individual, is going to mess everything up tonight,” Steratore said.

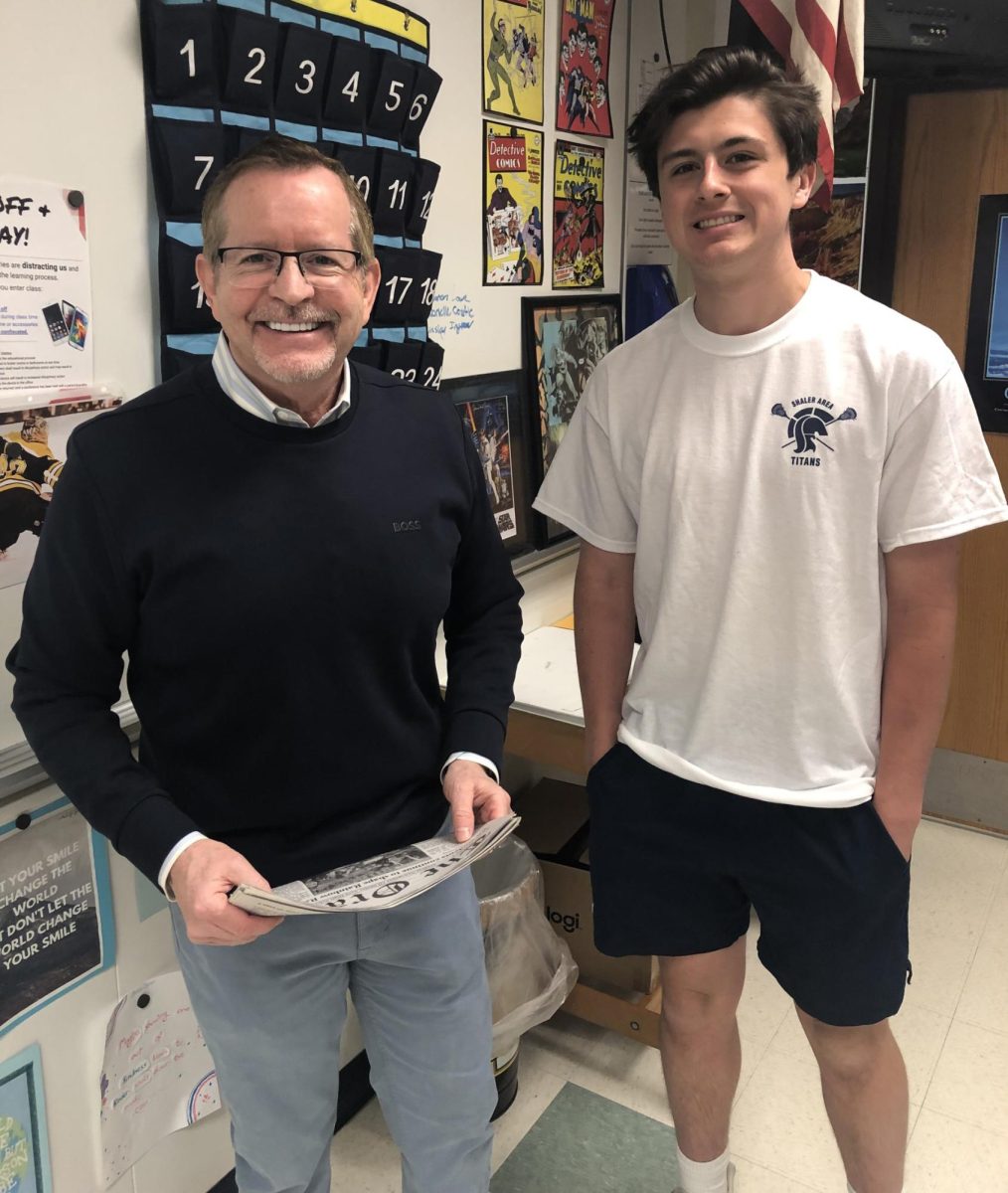

In addition to his role on television, Steratore has traveled across the country trying to raise awareness about a shortage of sports officials to the nation’s youth. He hopes to encourage America’s youth to develop a culture of appreciation for officials and become officials. Since so many athletes know and love the games they play, they are prime candidates to become officials.

“Part of why I retired was to try to get this message out. I want to talk to all the young athletes in America because 97% of high school athletes (stop playing) after graduating. If you’re an athlete, there’s a lot that you love about sports other than just playing.”

Along with encouraging young athletes to become referees, Steratore hopes that he can be part of a broader movement to stop hate of various forms and become a voice for empathy in general. Using his reputation as a renowned referee, Steratore seeks to make that change.

“Another reason I retired was to work with CBS, getting to befriend people like Jim Nantz, Tony Romo, who I never thought I’d get a chance to meet more than a couple times. I was really lucky to get on this stage,” Steratore said. “At this point in my life, the platform I have with CBS has allowed me to start making a difference in the lives of people that are willing to listen. If just 10% of people are willing to make a change, willing to listen, willing to stop hating, and willing to develop empathy for people in general, not just officials, it would be great for society.”

Ed Waterman • Mar 2, 2025 at 3:28 pm

Gene is the best at his craft. Period.