Shaler Area grad’s artwork going to baseball Hall of Fame

Piece, inspired by Black Lives Matter movement, shows Pittsburgh Pirates Sept 1, 1971 lineup — the first all Black and Latino lineup in MLB

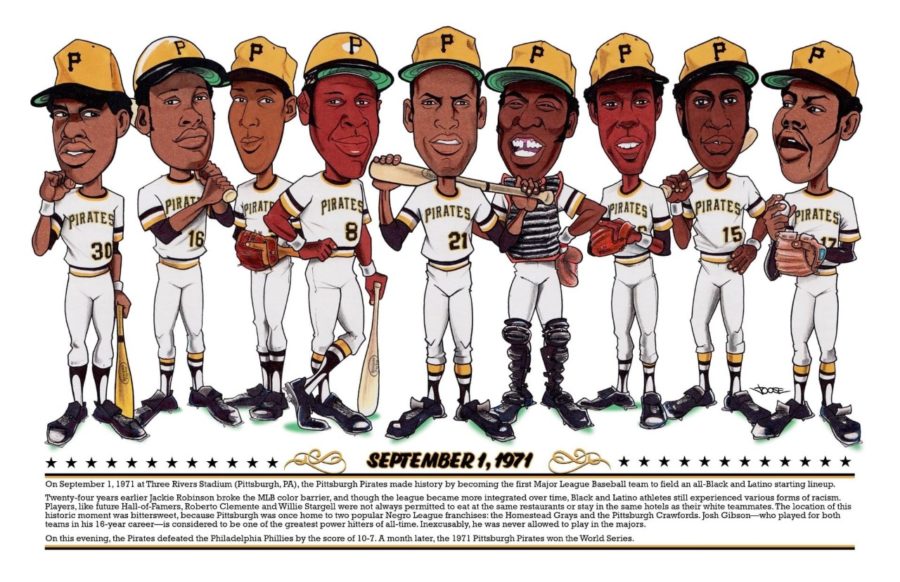

Jim Shearer’s caricature art of the first all Black and Latino lineup in Major League Baseball

Nestled away on Main St. in Cooperstown, New York, sits the famed Baseball Hall of Fame, which has been in existence since 1939. Home to some of the greats of the sport, it houses artifacts and plaques that represent the likes of Babe Ruth, Mickey Mantle, and Willie Mays. Now, another name can be added to that list: Jim Shearer.

Shearer, a graduate of Shaler Area and brother of Shaler Area High School English teacher Mrs. Anne Loudon, is more known for his connections to the music world. He hosted “VH1 Top 20 Video Countdown”, VH1’s “100 Greatest Artists of All Time”, and “100 Greatest Videos of All Time”, as well as numerous shows on MTV and MTV2. He now hosts “The Jim Shearer Show” on SiriusXM VOLUME, where he interviews musicians and industry talent, as well as talking about music, specifically music from the ‘90s.

Outside of music, Shearer is known for his love of sports, primarily Pittsburgh sports teams. It was this love, as well as his desire to capture the climate of today, that inspired him to create a drawing of the first-ever all-Black-and-Latino starting lineup in Major League Baseball history when the Pirates debuted it in 1971.

“When all of the Black Lives Matter protests were happening, it felt like a really positive thing in New York City, and then just looking on Facebook and talking to some people in Pittsburgh, it seemed like they didn’t have the right idea about it,” Shearer said. “When you brought up Black Lives Matter, they automatically wanted to talk about people burning buildings and I said, ‘No, you can’t think of the movement and protests as some bad seeds burning buildings. It’s about equality and lifting up black people on the same level as white people.’ I felt the best way to talk about it wasn’t necessarily to shout ‘BLM’ from the rooftops, but through Pittsburgh sports.”

The Baseball Hall of Fame contains a fan wing, where baseball fans and people alike can submit pieces of artwork or memorabilia to be displayed. While his dad helped him get the art to the public, it was Shearer’s uncle that made his work being represented in Cooperstown possible.

“My dad gave a copy [of my drawing] to my uncle, and my uncle is a baseball nut,” Shearer said. “This summer he went to the Hall of Fame and had a couple copies of it [on him]. Someone he was talking to said they had a fan wing of the Hall of Fame where fans could submit different pieces of artwork. He got me the business card of someone and I just emailed them to humor my uncle not thinking they would get back, and they did get back to me and said ‘We would like this for the permanent collection.’”

Outside of what it stands for and the impact it could have, a reason it was inducted is because of the beauty of the actual picture. It features Pirates such as Willie Stargell, Rennie Stennet, and Al Oliver in uniform with the date the all-Black-and-Latino lineup debuted, September 1, 1971, underneath their cleats. Featured in the middle, with four Pirates on either side, is Roberto Clemente. His position on the drawing and straight expression on his face was purposely down by Shearer.

“I put Roberto Clemente in the middle because he’s one of the greatest baseball players of all time and he happened to play in Pittsburgh, so to put him anywhere else I think would be disrespectful to a guy who was nicknamed ‘The Great One’,” Shearer said. “The reason I didn’t have him with a big smile plastered across his face is because when he played in Pittsburgh there were a lot of times where he was disrespected. Even though he probably liked playing in Pittsburgh, there were probably a lot of things that he didn’t like about Pittsburgh, so I gave him a game face in the middle.”

Also mentioned in the description of the drawing is Josh Gibson, who some say could be the greatest baseball player who ever lived. Gibson, however, never played in the Major Leagues because of the color of his skin.

“This picture is kind of nuts if you think about it. In 1971, the Pirates fielded the first Black and Latino starting lineup and it was only 24 years earlier that Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball,” Shearer said. “The reason I put Josh Gibson is because he is considered one of the greatest power hitters in the history of the sport. I think it was a shame that we basically had Babe Ruth playing in our backyard but he was never allowed to play in Major League Baseball.”

Outside of this drawing, Shearer has done pieces on the Steelers when they won Super Bowl XL and Super Bowl XLIII, as well as multiple caricatures of the Penguins when they won their last three Stanley Cups in 2009, 2016, and 2017. It was his father who helped him get these drawings out to the public, and that was the same for his art of the Pirates.

“I’ll send my dad 200 of my drawings and when he’s grocery shopping or at my nephew’s baseball game, he’ll strike up conversations with people and say ‘Oh, let me run to the car and get you a picture of this or that.’” Shearer said. “So I thought if I printed my dad a whole bunch of these pictures, it would be an easier way to talk about race in Pittsburgh without using Black Lives Matter, which felt like such a trigger statement for whatever reason.”

It is with his dad that Shearer remembers sharing his early sports memories with — memories that helped shape his love of sports today, inspiring the pieces he draws.

“The first memory I have is watching Super Bowl XIV with my dad between the Steelers and Rams. We had an old black-and-white TV. So that was the first football game I ever remember watching. I don’t think I made it until the end. I probably fell asleep because I was four or five years old,” he said.

Fast-forward to today, and Shearer remembers some of his most recent Pittsburgh sports memories, as well.

“In the early ‘90s, the Pirates finally made it to the playoffs because for years we couldn’t get over the Mets who were just a really good team in the mid-to-late-1980s,” Shearer said. “So we finally beat the Mets, and we were never able to get to the World Series. And then, of course, the Steelers’ last two Super Bowls were huge because the ‘70s Super Bowls always felt like more of my parents’ Super Bowls and Super Bowl XL and Super Bowl XLIII finally felt like my Steelers won the Super Bowl. Then of course the two Pens Stanley Cups in the early ‘90s were big and then the back-to-back not so long ago was also huge for me.”

Shearer’s pull to drawing started when he was young, describing himself as a “doodler” when he was growing up. Mainly in the 1990s, it was common for sports fans to wear or display caricatures of famous athletes of the day. One caricature artist that inspired Shearer was Bruce Stark, and Shearer was even able to buy a couple of pieces of art from Stark before Stark passed away.

“I guess I was so inspired by Bruce Stark that I wanted to create my own version of that and that’s why I started drawing sports caricature.”

This version is not just visually appealing, but it also has far greater meaning behind the players and words shown. In the end, it was that meaning that pushed Shearer to drawing his art.

“I drew it because it was my way of getting fellow Pittsburghers to talk about race,” Shearer said. “I want them to take pride in Pittsburgh [because] people may think that you can only fight for equality in New York or Los Angeles, but I want them to know that a very historic thing regarding race happened in Pittsburgh. This game happened in Three Rivers Stadium.”

Shearer has never been to the Hall of Fame before, and has not seen his work presented in Cooperstown. Yet, he cites that it is not the gratification that he gets from having his work there, but rather the impact that the art can have that is what strikes him the most.

“I’m not big on trophies and awards and stuff like that. But if it can get just someone to think and talk about race and get outside of their comfort zone for a second, that’s all I ever wanted from it.”

Dominic DiTommaso is an award-winning sports writer and columnist for The Oracle at Shaler Area High School. He first started writing sports columns for...

Michael Shearer • Mar 19, 2021 at 3:59 pm

I just want to applaud Dominic DiTommaso for his sterling article on Shaler’s Jim Shearer and the “Black Lives Matter” inspired artwok going in the Cooperstown Hall of Fame. It was a terrifically done piece of writing. I bet some day we may see Dominic as a sportswriter for “The Pittsburgh Post-Gazzette”. Dominic did justice for Jim and the reasoning behind Jim’s masterpiece. I am Jim’s dad and I am so proud of Jim and Dominic for portraying Jim so artistically in writing.